Of the remaining members of the family, the six younger children were admitted to the Workhouse immediately following Thomas’s inquest. They were entered into the register as.

William Henry aged 12, Charles aged 10, Elizabeth Jane aged 8, Daniel Burns aged 6, Valentine aged 4, Albert James aged 3

On the 28th August, less than a week after the neglect was uncovered, the Mercury had reported that the life of four year old Valentine Berry had been despaired of. He was placed under the care of Nurse Grace Nisbit Gribble, Matron at the fever hospital in the workhouse. Initially weak and exhausted, he gradually began to regain strength, to put on weight and to walk. The Mercury was optimistic about the progress of all the surviving children, but this view was somewhat premature.

At the end of October, Valentine caught a cold and his lungs became inflamed. He died on the fourth of November.

Three year old Albert James died of measles and scarletina just an hour or so later.

By the time the Aspinalls went to trial, their four youngest children were dead.

The week before the trial at the County Assizes, at the Freemason’s hall on Lime Street, just a few hundred yards from the courtroom, Mr Woodhead’s Parisian Gallery of Anatomy exhibition was advertising that a full- length waxwork model of one of the Aspinall children who had been starved to death in Eldon Place had just been added. Admission one shilling: sixpence to the working classes.

The trial opened at 1pm on Friday 13th December before Mr Justice Wightman. The case remained a cause celebre throughout the city. The courtroom was packed.

William and Mary were in the dock, both dressed in black. Henry Tindal Atkinson and William Brett, stood for the prosecution . The two men were most likely well acquainted, both barristers from London practicing in Liverpool for several years frequently appeared in court together, sometimes on opposing sides. Atkinson was more experienced, being more than twenty years Brett’s senior. In 1851 they had lived directly opposite each other in lodgings at Mount Street, less than two minutes walk from 55 Rodney street where William Aspinall and his family were inhabiting a similar property.

Defending William Aspinall was John Monk, a sixty two year old barrister from Derbyshire . Monk had initially been appointed to defend both prisoners. On the morning of the trial he realised that this was unfeasible. Given the coroner’s previous assessment about the strict division of responsibilities between husband and wife it was apparent that blame was going to be apportioned according to gender. There was a clear conflict of interest. The only hope of acquittal of either spouse was to attribute guilt to the other. Mary was quickly allocated the nearest available defence lawyer, John Simon.

Henry Tindal Atkinson opened proceedings for the prosecution by re-iterating the view of the coroner that the jury would probably be advised that it was up to the husband to provide the means of support and the wife to distribute it. He said that Emma may have died of neglect or some other act, perhaps hinting at the cold water that had been repeatedly been poured over Emma by seven year old Elizabeth Jane under the instructions of her mother.

Sarah Bell, the Aspinall’s next door neighbour gave evidence that she had seen the children almost naked and malnourished in the yard and that she had frequently heard quarrelling from next door, and had seen Mary Aspinall in a state of intoxication. Damningly she reported that Emma had died without being christened.

The testimony of John, the Aspinall’s eldest son, was very similar to the evidence he had already given at the coroner’s inquest. He added that his father cooked dinner on Sundays when he was home, making soup from pig’s cheek. He said his father often gave Emma a butty when she asked for one, he had never known him refuse her.

He said also that Emma sat on his mother’s knee and was fed from her plate. He thought that Emma was given bread every day.

John recounted the same stories of drunkenness neglect and quarrelling, with his mother arguing that she wasn’t given sufficient money. When questioned by Mary’s defence lawyer He said that he had not witnessed cold water being pumped over Emma and when he had seen her in the sink it was for the purposes of being washed. There was a carpet in the yard for the children to play on. John and his father were fed separately from the children during the week.

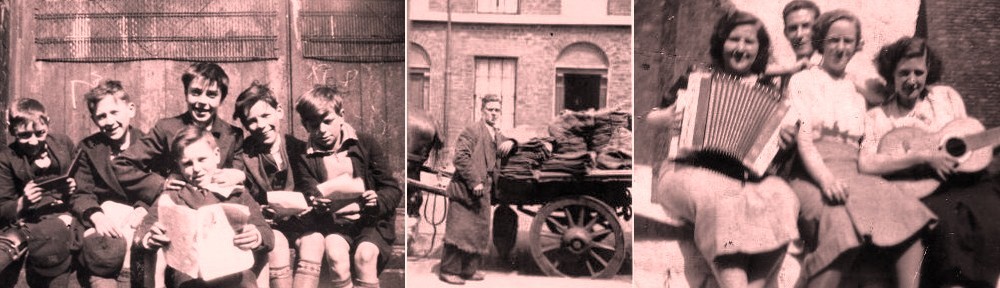

Then there was an additional witness: twelve year old William Henry Aspinall, so small and fragile he could have been taken for a seven year old and he had to be placed prominently where he could be seen to give evidence. William stated:

“I lived at home with father and mother. Mother usually got up at twelve o’clock in the day. I have seen my mother tipsy often. What I had to eat I had with my brothers and sisters. We had porridge in the morning for breakfast. ‘taties for dinner and bread and coffee for tea.”

At this point, according to the Carlisle Patriot, the child looked at his parents in the dock and sobbed bitterly. The Liverpool Daily Post reported that there was scarcely a dry eye in the courtroom.

Collecting himself, William Henry continued with his testimony. Often there was no dinner, and when he asked his mother for some she told him to go out and get it himself. Emma cried often at breakfast when his father was there. He had not seen his mother do anything to Emma but he had heard her refer to Emma as ‘a picture of misery’. He had seen the other children take food from Emma. His sister Mary gave Emma bread but Emma had crumbled it in her hand and wasted it. He recalled his father giving his mother £2 about four weeks before Emma died. He had not seen Elizabeth pump cold water over Emma.

He recounted hearing his parents quarrelling. His mother had said she should have mutton chops and port wine. His father said he gave her enough for that. He had not seen his mother throw anything at his father. This was significant because William had alleged that he and his eldest son often had to leave the house and walk the streets at night when Mary had thrown things at them.

Much of the children’s evidence about their mother was damning. The children testified that they had seen both parents tipsy, though their mother more often than their father. All the children reported that they had seen their mother frequently drunk, and that they had seen their father hand over money for the housekeeping. William Henry said: “I remember my father give my mother £2 a short time before my sister died. As soon as my father went out, my mother sent me out for some gin.” John confirmed that he handed all his wages over, sometimes to his mother, but lately to his father. He had seen his father give his mother a sovereign about three weeks before.

Mary junior also mentioned the £2 given by her father, but on closer questioning by Mr Simon, her mother’s defence lawyer, she said that it had been about five weeks ago, and that her father had taken 28s of it back for rent. She stated, “when my father had to return without dinner, sometimes mother would get dinner for us. If she did not, it was because she had no money,”

In many ways, Mary junior’s testimony was the least harmful towards her mother.

Much was made of Mary being given money by William, but was it enough to feed a family? If he did withhold it, was it, as he claimed, because she spent it all on alcohol? There is no doubt that she had a serious drink problem.The children recounted stories of William buying and cooking food and making soup from pig’s cheek on Sundays, but it was clearly insufficient to stave off tragedy. Mary reported that her mother had breast-fed the baby but had insufficient milk.

The defence tried to suggest that Emma’s weight loss and death might have been caused by scrofula, or mal-assimilation of food, but the three surgeons who gave evidence, George Kemp, Edward Brown, and Frederick Dicker Fletcher all insisted that the cause of death was lack of food.

After a summing up by the judge that strongly leaned towards her guilt, Mary was convicted. William was acquitted.

On the charge of causing the death of Thomas Ratcliffe no evidence was offered by the prosecution and both were acquitted.

The judge, Mr Justice Wightman, in his summing up, had advised the jury that it was the husband’s role to earn the money for the upkeep of the family and it was the wife’s responsibility to manage it. His direction was that blame should be apportioned to one or the other of the two parties and not both. Given that a verdict of not guilty was unlikely, The jury chose Mary as the parent at fault.

Many people felt that William had got off lightly.

As Mary’s defence lawyer had pointed out in court:

“What kind of man was it that who would seek to screen himself from responsibility in a case of this kind by saying to the wife, ‘I gave you money, that was all I had to do: I saw you get drunk with it?'”

The Daily Post reported the sentence as an ‘anomoly’,

“On Thursday last, a husband and wife were indicted for having caused the

death of their child by starvation. The learned Judge ruled that, as the

husband had given the wife money to buy food for the child, he could not be found

guilty, although he must have observed daily for months, that the child, and

some of his other children, were wasting away”.

They concluded that “If the Judge’s speech be reported correctly, the law seems at variance with a father’s duty….”

The relevance of Mary’s infidelity to her children’s deaths was never entirely made clear, but it seems to have been used as evidence of her general lack of morality and the reason her family life went into decline. It no doubt counted against her with the judge and jury.

Sentence was passed on Mary a few days after the trial. She protested her innocence proclaiming,

“I am an injured woman. I never wronged the children; I never misspent my husband’s earnings.”

During the inquests he had persistently maintained that William had been cruel and abusive . She had previously claimed that she had broken the windows in the house in attempts to call for help and escape from his violence. She had said that she had tried to leave him in the past and would have had the means to support herself, but he had prevented her from doing so and had sold her possessions and withheld money from her

Mary was sentenced to two years hard labour for the manslaughter of Emma, the first and last weeks of her sentence to be served in solitary confinement.