Liverpool is the home of Britain’s oldest Black community, mostly centred around Toxteth in the south end of the city. Some families are able to trace their heritage back for many generations. Liverpool’s role in the slave trade resulted in ship owners and traders bringing enslaved Africans here to work as servants or to be sold at auction in coffee houses near the docks. The first known burial of an enslaved person was in 1777 at St Nicholas Parish church overlooking the seafront.

During the American War of Independence, some slaves remained loyal to Britain rather than support their slave masters, although Britain had, of course, been complicit in their enslavement. In 1775, a proclamation was issued offering freedom to all slaves who deserted to serve in the British army. After the British surrendered, some of these men were shipped out to Britain. Most went to London, but some settled in Liverpool. Slavery was still legal in Britain at that point and was not abolished until 1807. Many of Liverpool’s streets are still named after its prominent slave traders and the wealth accrued by slave trading families enabled them to wield power and influence in the city up until the end of the nineteenth century.

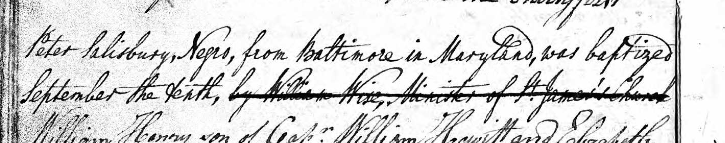

It is difficult to estimate the size of the Black community in the eighteenth century, and often the only clues are in parish records, for example, an entry in St. James (Toxteth) Parish Registers on Sept 07th 1783:

‘Peter Salisbury, Negro from Baltimore, Maryland.’

The Nineteenth Century

As a major seaport, Liverpool was visited by seafarers of all nationalities, some of whom settled here and married local women. This continued into the nineteenth century, but even then it is hard to establish numbers. Although in America, race was recorded as a category in the census, this was not the case in the UK. Often place of birth is the only clue to identifying Black residents, but this would not of course apply to those who were British born.

Herman Melville, the author of Moby Dick, wrote the semi-autobiographical novel, Redburn, based partly on his experience as a sailor docking in Liverpool in 1839. He was surprised to find very few Black people in the town, but this was likely to have been in comparison to New York where he had spent most of his life. He found Liverpool to be a tolerant place:

Speaking of negroes, recalls the looks of interest with which negro-sailors are regarded when they walk the Liverpool streets. In Liverpool indeed the negro steps with a prouder pace, and lifts his head like a man; for here, no such exaggerated feeling exists in respect to him, as in America. Three or four times, I encountered our black steward, dressed very handsomely, and walking arm in arm with a good-looking English woman. In New York, such a couple would have been mobbed in three minutes; and the steward would have been lucky to escape with whole limbs. Owing to the friendly reception extended to them, and the unwonted immunities they enjoy in Liverpool, the black cooks and stewards of American ships are very much attached to the place and like to make voyages to it.

Being so young and inexperienced then, and unconsciously swayed in some degree by those local and social prejudices, that are the marring of most men, and from which, for the mass, there seems no possible escape; at first I was surprised that a colored man should be treated as he is in this town; but a little reflection showed that, after all, it was but recognizing his claims to humanity and normal equality; so that, in some things, we Americans leave to other countries the carrying out of the principle that stands at the head of our Declaration of Independence.

As part of his series, ‘The Uncommercial Traveller’, Charles Dickens published an article in 1860 about a trip to Liverpool where he met sailors or ‘Jacks’ of various nationalities. He is taken to a small public house where he encounters ‘Dark Jack’ and his white female companion, the ‘unlovely’ Nan:

The male dancers were all blacks, and one was an unusually powerful man of six feet three or four. The sound of their flat feet on the floor was as unlike the sound of white feet as their faces were unlike white faces. They toed and heeled, shuffled, double- shuffled, double-double-shuffled, covered the buckle, and beat the time out, rarely, dancing with a great show of teeth, and with a childish good-humoured enjoyment that was very prepossessing. They generally kept together, these poor fellows, said Mr. Superintendent, because they were at a disadvantage singly, and liable to slights in the neighbouring streets. But, if I were Light Jack, I should be very slow to interfere oppressively with Dark Jack, for, whenever I have had to do with him I have found him a simple and a gentle fellow.

Dicken’s racism and stereotyping notwithstanding, his account at least provides evidence of the presence of Black sailors in Liverpool during this period.

The Twentieth Century

Race Riots

On the evening of June 05th 1919, there was a disturbance in licensed premises on the corner of Bailey street and Grenville Street when a Black man was stabbed by a Scandinavian. A fight broke out between the two groups of men. A policeman intervened and was badly slashed about the head and hands. Tension had been brewing for some time. between the two groups.

After the fighting had been broken up, the Black men returned to the hostels in Upper Pitt Street and the surrounding streets where most of them were resident. An angry mob of white people then gathered in this area. The white rioters all appeared to be locals. The Scandinavians had retreated. One report said that ‘strained relations have existed between the white population of the negro colony in this quarter for some time, due, it is stated, to the familiarity which exists between many of the negroes and white girls’.

What exactly happened that night is difficult to establish. Initial newspaper reports say that shots were fired in from premises on Upper Pitt Street, injuring three policemen. Later evidence given in court by Thomas Brown, the policeman most seriously injured, tells a different story. He said that he sent to the scene of the riot where they were able to disperse the White crowd on the corner of Nelson Street without difficulty but a group of about fifty Black men resisted attempts to break them up:

One of the coloured men struck a constable on the shoulder with a stick, and broke the stick in so doing. I ran towards the coloured man who had thus used his stick, whereupon another coloured man molested me with a revolver, which he drew from his right-hand pocket. I turned on him, and with my baton struck his right wrist, so that he let the revolver drop, but, catching the weapon in his left hand, he aimed at my chest and fired. The bullet struck me under the lower lip, knocked out three of my teeth, and entered my neck at the side of the spinal cord. I fell to the ground, bleeding profusely, but did not lose consciousness. A girl in the crowd tore off a part of her skirt and pushed it into my mouth, thus materially checking the flow of blood.

Three policemen, including Detective Inspector Burgess raided a lodging house at 18 Pitt Street. Twenty-four-year-old Charles Wotten and another man fled from the house. They ran towards the dockside pursued by the police. The men were chased by an angry mob throwing missiles. Burgess claimed that there was a crowd of around two thousand people, ‘mostly women, seething with excitement and calling for vengeance on the negroes’. This is difficult to equate with PC Brown’s testimony that the White crowd had been dispersed without difficulty.

At the docks, the police got hold of Wotten, but he was wrenched away by the mob. It was unclear whether he was pushed into the Queens dock, whether he fell in the scramble, or whether he jumped, believing it to be his only hope of survival. He swam for a while in the water. A detective climbed down and was about to pull him out when a stone thrown from the crowd struck Wotten on the head and he sank. His body was later recovered with grappling irons.

The Liverpool Echo, writing about the conflict, alleged that there were between four and five thousand Black men living in this part of Liverpool. This was contradicted in court by ‘Mr D.Y. Aleifasakure’ [T.D. Aleifasakure Toummanah], the Secretary of the Ethiopian Hall, who said that the numbers were between five and six hundred. The men in hostels were British subjects, many of whom had served in the forces during the war. They were mostly sailors, cooks, stewards and firemen who had arrived in Liverpool as employers of the Elder Dempster shipping company, but were now unable to get work.

Charles Wotten’s inquest appeared to be a cursory affair. Nobody was charged with his death and the coroner directed they should return a result of death by drowning. He was buried at Anfield Cemetery on 11th June. A number of people, Black and White, were, however, charged in connection of the events that evening.

Sixteen Black men faced charges of rioting, with further charges of attempting to murder a policeman. Their case was adjourned for a week, when one of the men, Benjamin Bennett, was discharged after witnesses failed to identify him. The case was adjourned yet again, and reconvened in July at a lecture theatre at the Southern Hospital where Police Constable Thomas Brown was still being treated for his injuries. Brown was brought in in a wheelchair. He had a number of teeth missing where the bullet had entered through his mouth. The men were lined up and made to parade past him. Brown identified Sonny John as the man who shot him; Charles Murray as the man who broke his stick across the shoulder of another constable, and Eddie Scott as one of the men armed with an iron bar.

Tensions remained high with many local Black people in fear for their lives. Mobs patrolled the streets, according to one police report, ‘savagely attacking, beating and stabbing every negro they could find’. A week after the first riot, another disturbance broke out on Soho Street and twenty-nine-year-old ‘coloured man’ Charles Fitzroy Gardner was arrested and charged with attempting to do grievous bodily harm to a police constable. The court heard that he was waving a gun a revolver at a crowd. When PC Andrew approached him, he said, ‘Stand or I fire’. Andrew, with the help of another policeman, managed to disarm him. Gardner argued in court that he had no intention of firing the gun, he was only trying to frighten the crowd. The jury found him not guilty. The judge made a point of saying that he agreed with the verdict although he diplomatically commended PC Andrew for his courage. The charges against Gardner were serious ones. Given the lynch mob mentality prevalent at the time, his acquittal might seem surprising, but this was probably the very reason that judge and jury found it credible that he was acting in self defence. Many academic articles on the riots have cited cases of racism by the Liverpool police.

Rioting broke out that summer in several other ports including Newport and Cardiff.

The alleged rioters from the night that Charles Wotten was killed were remanded and the cases went to the assizes in November. The case against another man was dismissed through lack of evidence. The remaining men were defended by Black barrister, Edward Theophilus Nelson.

Nelson, an Oxford graduate with a practice in Manchester was born in British Guiana on 22 October 1879* Nelson, himself the descendant of slaves, was able dismantle aspects the prosecution evidence, most of which was based solely on witness identification. Ten of the fourteen were convicted, with sentences of between eight and twenty-two months, some with hard labour. Sonny John, who PC brown identified as having shot him, was acquitted. So was Eddie Scott, who Brown identified as wielding an iron bar. The defence was funded by the African Progress Union, a London-based civil rights group led by Liverpool-born Black activist, John Richard Archer, former Mayor of Battersea and the first Black Mayor in London, himself a former seaman.

A few days later, the trial of the White defendants took place. Twenty men and one woman were found guilty and received sentences of between four and thirteen months, some with hard labour. The only exception was seventeen-year-old James Durie who was sentenced to three years borstal. It may appear that awarding similar sentences to Black and White rioters was an indication of even-handed justice, but the White rioters were not fighting for their lives that night or hounded from their homes to their death. They freely participated in the disturbance because of violent and racist motives. Judge McCardle, presiding, did acknowledge this to some extent, saying that, ‘instead of helping in the maintenance of order, the prisoners took a share in attacking black men living in the city and in the scandalous riots that took place’.

A plaque in memory of Charles Wotten was unveiled on Liverpool’s Waterfront in 2017.

* Some sources say Nelson was born in 1874 or 1878, I have taken this date from the 1939 register.

Eugenics and Anthropologists

The 1925 Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seamen) Order made it more difficult for Black seamen living in Britain as they were ordered to carry documentation proving their rights as citizens, but many Black sailors remained in Liverpool and married local White women. Their offspring were perceived as a social problem by the growing eugenics movement and by some social welfare organisations. The Liverpool University Settlement, founded in 1908, began to focus on the ‘plight’ of Liverpool ‘half-caste’ children.

Rachel Fleming, an anthropologist from the University of Aberystwyth undertook some field work in Liverpool’s black community and those of other seaport towns. She visited Liverpool schools in the South end of the city and measured the head shapes and other characteristics of children of mixed Chinese and White parentage and Black and White parentage. Her subsequent article published in the Eugenics Review details and analyses features such as eye colour and shape, skin colour, descriptions of lips, hair colour and texture. The article makes uncomfortable reading and it is difficult to see what use this kind of information could serve. Fleming is more positive about the children of Chinese heritage than those of Black heritage. At the end of the article she focuses on the difficulties of half-caste girls in finding employment:

If homes could be established where girls of this type might be boarded and taught useful occupations during adolescence it would at any rate mitigate the difficulties and dangers imposed upon them by our social conditions. This is a problem which I hope, will come within the scope of this society’s activities.

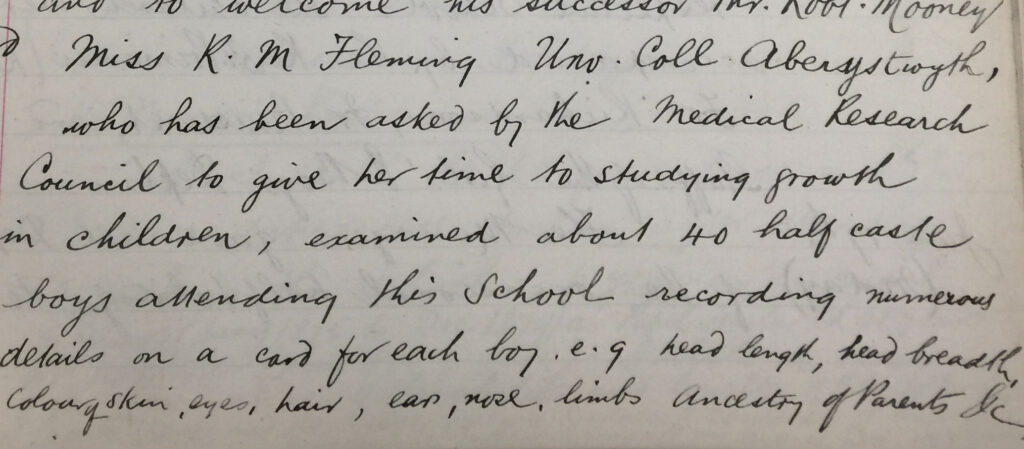

Fleming, continued her work, visiting St Peter’s Roman Catholic school in Seel Street later that year. The school log book records:

Miss R.M. Fleming Unv. Coll Aberystwyth who has been asked by the Medical Research Council to give her time to studying growth in children, examined about 40 half-caste boys attending this school recording numerous details on a card for each boy, e.g. head length, head breadth, colour of skin, eyes, hair, ears, nose, limbs, ancestry of parents.

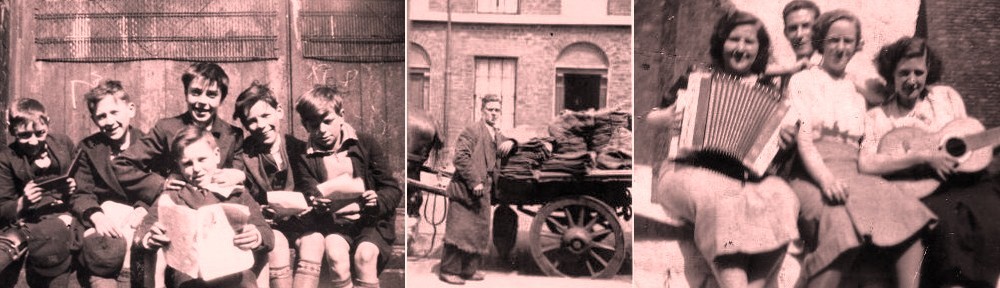

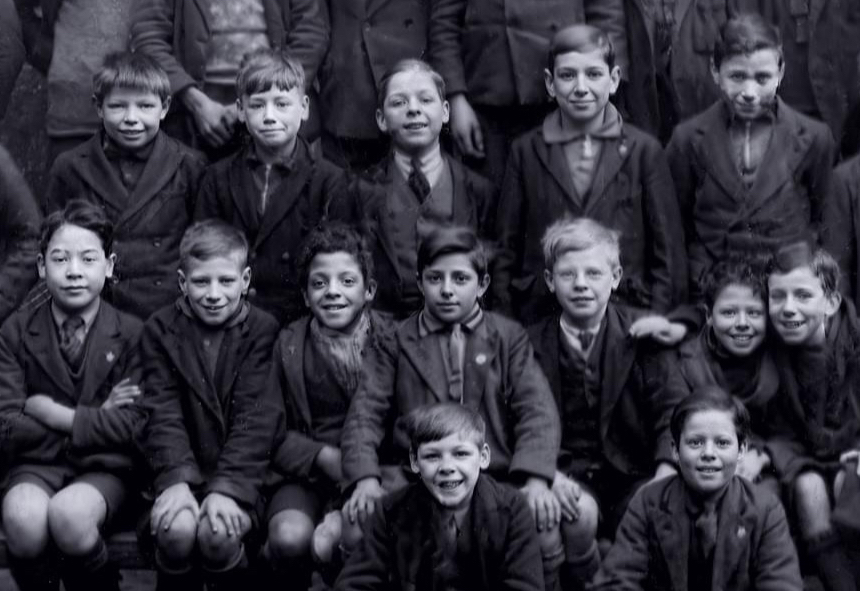

This is a section from a class photo at St Peter’s RC School in 1930. These boys, who moved up to junior school in April 1927, would almost certainly have had their heads measured by Rachel Fleming and some of their families may well have been the subject of Muriel Fletcher’s research.

In December 1927 a meeting took place at the Liverpool University Settlement. It was attended by representatives of numerous agencies including the police and the education authorities. Rachel Fleming persuaded those present of the need to tackle the ‘problem’ of half-caste children. The meeting led to the founding of the Liverpool Association for the Welfare of Half-Caste Children. The Association’s chairman was Professor Percy Roxby from the Department of Geography at Liverpool University. Other members were, G.E. Haynes; Reverend G.H. Bates, the vicar of St Michael’s in Upper Pitt Street; Father Primavesi from St Peter’s Church, Seel Street; Miss Black from the School of Social Science; Miss Hardwick and Miss Moss from the Diocesan Board of Moral Welfare; William King, the Headmaster of South Church School; Miss McCrindell; the Warden of the David Lewis Club and Miss Peto and Miss Tidd Pratt, from Women Police Patrols.

The Association agreed to commission further research from Muriel E. Fletcher, a graduate of Liverpool University’s School of Social Science who was then working as a probation officer in Stoke on Trent. Her brief was ‘to make a full survey and to explore both the nature of the problem and possible solutions to it’. Her research focused on the conditions and economic status of ‘half-caste’ families in Liverpool paying particular attention to the children of these families and their future prospects.

In 1930, Muriel Fletcher produced her Report on an Investigation into the Colour Problem in Liverpool and other Ports. Fletcher identified 450 mixed race families in the city but only interviewed 98 of them. With chapter headings such as ‘The Extent of the Problem’ and ‘The Women who Consort with Coloured Men’ it painted an almost totally bleak picture of Liverpool’s Black community. Like Rachel Fleming three years earlier, instead of looking positively at integration, Fletcher viewed mixed race families as a ‘problem’ to be addressed. Fletcher highlighted issues such as employment discrimination, particularly how it affected young women. But rather than seeing the solution as tackling racism, she focused on how to make the women more employable. Her uninspiring twice-weekly handicrafts class with five bored teenage girls predictably ended in failure, improving slightly when a financial incentive is offered. One of her conclusions is that the girls ‘easily tire and lack the power of application’. Most of the report is too offensive and overtly racist to quote from. It did serious and enduring damage to race relations in Liverpool and eroded trust between the community and welfare organisations.

The committee that commissioned the Fletcher report included two members of Liverpool Women’s Police Patrol. This was an organisation founded in 1914. It received an annual grant from Liverpool Corporation’s Watch committee. It consisted of women volunteers who patrolled the streets to try to prevent young women and girls from falling into vice.

The Women’s Police Patrol AGM in 1945 released an annual report warning of the dangers to young girls in Chinese and foreign eating houses in the South end of the city where ‘they were generally to be found in the company of Chinese seamen’. It warns that ‘The fluctuating foreign population presented a grave menace to young girls’. There were also concerns about alcohol drinking among girls. ‘There were few signs of real drunkenness, but many juveniles appeared in public-houses with coloured men’.

Although their intentions appeared to be, the twentieth-century equivalent of ‘saving fallen women,’ their ethos about preserving women’s respectability appeared to be informed by the same kind of racist ideology that underpinned the Fletcher report.

The 1980s brought the Toxteth riots. The area, already deprived, was hard hit by depression and unemployment in the Thatcher era and the relationship between the community and Merseyside Police was one of distrust due to their heavy-handed stop and search policies. Following the riots, Michael Heseltine was appointed Minister for Merseyside and initiatives such as the International Garden Festival followed in 1984. Despite extensive regeneration, the area remains economically deprived. Its diverse community remains proud of its history.