At the end of the war soldiers returned from the trenches to an uncertain future. While William was serving his country his brother, Peter, died when the Lusitania was sunk by a German U-boat, his father passed away after more than ten years of very poor health and Alice, his youngest sister, married and left Toxteth. William, fresh from the horrors of war returned home to a family he could hardly recognise and, due to already cramped living conditions, he found there was no room at the inn.

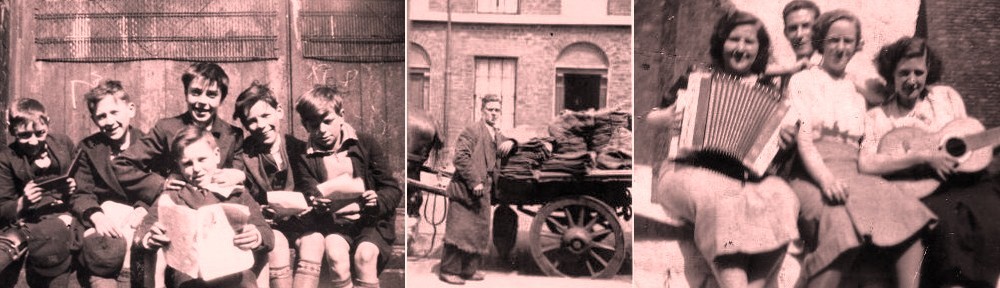

Like many single people William was forced to live in a series of lodging houses. He returned to the dockside to look for work, but high unemployment meant that regular work was extremely difficult to find. His sisters supported him as best they could, but they were struggling to provide for their own families. Sarah and her husband, John, had four children. Mary Jane, Peter and their nine children were living in a two bedroom house in Brindley Street and Alice, newly married with one child, had moved to Kirkdale.

William, a quiet man who found public speaking difficult, once described himself as more of a soldier than a speaker, but, due to a lack of regular employment, this quiet man reached a new level of bravery when he had a brief career on the stage. In 1925 he performed in ‘khaki’, a comedy drama by Ernie Lotinga, at the Hippodrome theatre Gloucester.

In 1929 Victoria Cross holders were invited, by the Prince of Wales, to attend a dinner at the Royal Gallery of the House of Lords. William was very keen to attend, but lack of funds and suitable clothing made this seem unlikely. A newspaper report outlined how Private Ratcliffe walked Liverpool docks every day looking for work, but he was lucky if he got two days a week and the suit he wore was the only one he possessed. After this publication the people of Liverpool rushed to his rescue and donated enough money to kit him out in a new suit suitable for the occasion.

Sometime around 1945, when working at the docks as a Stevedore, he was involved in a very serious accident. William sustained injuries to his neck, spine and pelvis and was left with a severe hearing problem when two one ton bags of castor seed fell and crushed him. His family tell a story of how he was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital and was left on a trolley. However, he later alarmed a nurse by sitting up. Nobody is completely sure if there is any real truth in this story.

After the accident William was declared medically unfit for work and received a pension of £2 a week. Around 1953 he moved to St Oswald Gardens to live with his sister , Sarah. Here he had a network of support from three generations of women, Sarah, her daughter, Margaret Walsh and Margaret’s daughter, Noreen,

On 26th June 1956 he attended the Victoria Cross Centenary Celebration at Hyde Park and was accompanied by Margaret and Noreen. On this occasion the Victoria Cross Association paid for his suit and accommodation.

When Sarah passed away, in 1955, Margaret and Noreen took on more responsibility to enable him to live independently.

Towards the end of his life William would spend his evenings in the local pubs. His family were worried that he was becoming confused so they would regularly check that he had returned home safely. One cold evening in mid-March 1963 Noreen, was unable to find him and, concerned for his welfare, contacted the police. Sadly, he had slipped on some ice and had been taken to Broad Green hospital. About a week later he was transferred to Kirkdale house, 241 Westminster Road and he died there on 26th March 1963.

William had a Military funeral at St Oswald’s Church, Old Swan, Liverpool. Major Ryan, soldiers from the South Lancashire Regiment and a small group of mourner attended. He was buried with his sister, Sarah and her husband John Humes at Allerton Cemetery and the grave is looked after by his great niece, Noreen Hill.