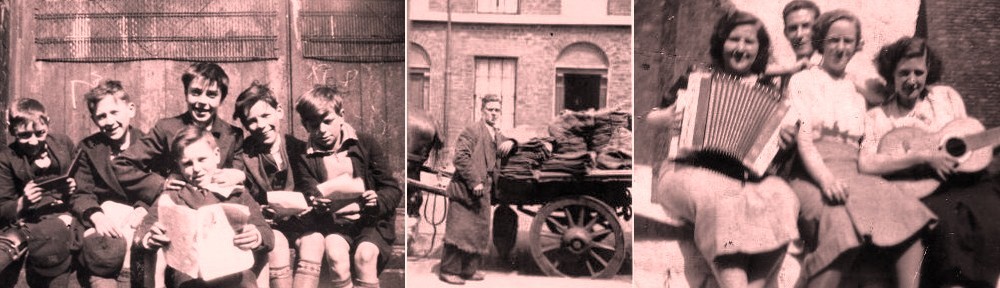

Philip’s War

Philip recalls his experiences of being evacuated during World War Two

Part One: The Leaving of Liverpool

The 1930’s wasn’t a really good time to be born; Britain had not yet recovered from the First World War, and there was mass unemployment everywhere. In Liverpool, during this period, most young men who were unemployed had to attend what was known as ‘Dole Schools’. It was here that they were given a choice of two trades; painters & decorators or shoe repairers. I often wondered if the saying ‘A load of old cobblers’ was born out of this period, it seemed very apt, anyway. Unemployment continued in the same vein up until about 1938, it was during this time that job creation began to increase, sadly the reasons behind this upturn was the preparation for war.

As a child I knew nothing of war, it was just something that older people often talked of, however, the reality soon came home to us. Policemen started to visit schools to inform the children that in the event of war, we would have to start taking precautions. Gas masks would have to be carried at all times in case of sudden attack and if the situation was prolonged, then we would have to be evacuated from the City to a safer place to live. The gas masks were jet black for the over fives and coloured ones for the younger children. The coloured ones were fashioned in the style of the popular cartoon character ‘Mickey Mouse’.

Child’s Gas Mask © IWM (EQU 3643)

The policemen would demonstrate how to put the mask on quickly in the event of an attack. There was an air of excitement on first receiving our masks, however the novelty soon wore off as the masks were very uncomfortable. After only 3 or 4 minutes the mask would shrink onto the shape of your face leaving it bathed in sweat. We had a baby at home, even one so young had to endure the dreaded gas mask. His mask was like an old fashioned diving suit, there were no arms or legs, he was put inside and laced up. There was a pump on the side, which had to be continually operated to keep the baby alive inside.

I remember the third of September 1939 as if it were yesterday. The Prime Minister, Mister Chamberlain, had made his famous declaration of war speech. By about three o’clock The Empire News, which was printed in Manchester was out on the streets in record time. The newspaper boys were running through the streets shouting “Extra, Extra , Read All About It”. How everyone who had lived through the First World War felt at this time was difficult to grasp; for the likes of us, there was a feeling of great excitement but this was short lived as eventually the reality of ‘evacuation’ hit home.

In the weeks that followed, we had it drilled into us, what evacuation really meant; it was to be no holiday. Each child was given a list of clothes that they would be expected to take away with them, I regret to say, the list bore no resemblance to what was in my clothes cupboard at home. Needless to say, my ever-loving mam miraculously managed to get hold of most things. At the time it didn’t occur to me that she probably had to go without in order to provide everything on the list. At school we were each given a large sheet of brown paper and a piece of string to wrap our clothes in; two labels, one for the parcel of clothes and one to be pinned to our coat. We had to write our name and the schools name on our box containing the gas mask; this done, we were now ready.

A couple of days later, over two hundred children from our school were marched in line to Lime Street Station. On arrival, we discovered that there were many hundreds more from all the other schools in the area. Many of the Mothers had found their own way to the station in order to say that one last goodbye to their precious children; the pain and anguish on their faces all too evident. Over at the ship builders Camel Lairds the new Mauritania had recently been launched, had it been this day, there were enough tears on Lime Street to have floated her. Suddenly, the station tannoy called out “All aboard, mind the doors”, then the shrill of the guards whistle and the train started to pull away. Although we were not really aware as to what was happening, the haunting screams of many of the children, gave a sense of deep fear and insecurity, an insecurity that could only be addressed by the loving arms of ones own mother.

During the journey volunteers tried to pacify us with sweets, they also provided milk, sandwiches and cake. Within a short while we arrived at Crewe, here we were transferred to buses and taken on the last leg of our journey. In my case the journey ended in a village called Sanbach. We were herded into the local village hall to be greeted by our prospective guardians for the duration of our evacuation. All the ladies seemed well spoken and well dressed; it seemed like a very ‘posh’ area, very different to what we’d been used to. The process of selection was reminiscent of a cattle market, children being poked and prodded by these ‘well to do’ women. We were labelled as being too fat, too thin, too big, too small or just plain grubby looking. It seemed obvious that these ladies were merely doing their duty but behind it all, many of them resented the fact that they were going to have uninvited guests walking all over their lovely homes.

© IWM (D 3106) Ministry of Information Photo

I was picked out by a Mrs Burgess, she certainly seemed to resent the fact that I would be interrupting her cosy lifestyle; she made it clear to me on the way home that I would have to do as I was told. She had a child of her own called Kenneth, he was about my age; like his mother, he too made it clear that I was not welcome. It was only a few hours before, that I’d left my own dear Mam, in tears, waving to me at Lime Street Station; here I was in a strange town, with strange people, unwelcome and certainly unloved. To be fair, Mr Burgess was a really nice man, he seemed to see the difficult situation that I was in; I got a real sense of genuine sympathy from him, although he never showed it in front of his wife. Privately, he took great delight in explaining to me about the process of growing vegetables and tomatoes. Like me, Mr Burgess also seemed somewhat downtrodden.

Soon after arriving, it was my job, along with Kenneth, to go and buy the potatoes and vegetables from a farm about half a mile away. The farmer was a kind old man who always presented us with three or four windfall apples, a rare treat. One day, I was sent along on my own; as it happened, on this particular day the farmer was not around so his wife dealt with me, for some reason she didn’t supply me with any windfalls.

My best friend, Joe Ducket had been evacuated to a farm some distance from me. Joe was one of the lucky ones; a lovely old widow who was very kind to him had taken him in. On my return from the farm with the vegetables, I passed Joe’s house, he was sitting on the garden wall eating an apple. After a brief chat, Joe gave me the core of his apple to finish off on my way home. As I got to Mrs Burgess’s house I had just finished the core and threw the remains into the hedge. I was unaware at the time that Mrs Burgess had witnessed this. I walked up the path and handed over the potatoes and vegetables; Mrs Burgess asked me where the windfalls were, I replied that the farmer had not been there and his wife had not given me any. Mrs Burgess exploded with rage and started to punch me like a woman possessed; all her pent up resentment seemed to come out in that moment. She was screaming “I saw you eating the apples coming up the road, you little liar!”

By now blood was streaming from my nose and mouth; I knew I had to get away. I made my escape and ran back to Joe’s house, he got me a flannel and helped me to clean up but the blood continued to flow. I asked Joe to find me some paper, an envelope and a pencil. Together we went down to the canal and I wrote a letter to my Mother, telling her of the unhappy episode. As I wrote, blood dripped onto the paper, proof if it was needed that I was telling the truth. I didn’t have a stamp but just prayed that the post office would deliver the letter anyway. Heavens knows what my Mam thought when she opened the blood stained note!

I told Joe that there was no way that I would be going back to Mrs Burgess; he suggested that I come back to his house. When we arrived, the kind old lady with whom Joe was staying, was just returning from a trip to town; when she saw the state of my face she said, “Well, you’re going to have to stay here until your Mother arrives”. With that, Mr Burgess arrived to take me back to the house; he too looked shocked at the state of my face. He begged me to go back, saying that his wife was deeply sorry for what she had done. The kind lady reluctantly agreed to let me go and off I went back to the house with Mr Burgess. On arrival I ran straight up to my bedroom, fearful of repercussions. All I heard from downstairs were raised voices; at last Mr Burgess seemed to have stood up to his wicked wife. The next day my Mother arrived and left Mrs Burgess with no doubt about how she felt about the treatment I had received. She told her that, as far as she was concerned her son would be a lot safer in Liverpool despite the falling bombs. Within a few hours I was back home in Liverpool. The smell of the Mersey never smelt sweeter.