In the early hours of Friday 24th August 1855, a lone woman lurched out of the darkness of a back alley behind Eldon Place in Liverpool, accosting two policemen on night duty on the corner of Vauxhall Road.

It had been a long night for thirty one year old John Metcalf, and his colleague, James Caldwell. Their shift had started at 9.45 and they still had several hours to go. They were used to dealing with a range of volatile behaviours, working in one of the poorest areas of the city, so their initial impatience with the clearly intoxicated Mary Aspinall was perhaps understandable.

Mary harangued the two policemen, with an account of her husband’s unacceptable behaviour, how he had had mistreated her and locked her out of the house, pleading with them to escort her home and protect her. Caldwell asked a few cursory questions but had already made his assessment of the situation. He told her dismissively that the police did not interfere in family quarrels, warning her, “You are drunk, you had better go home.”

Mary then made a startling claim. She said that her husband had murdered one of her children by starving the child to death and then kicking it when it had cried for bread. Another of her children was barely breathing and, she added, would most likely be dead by morning.

The two constables, with a new-found sense of urgency, went hurriedly with her to 64 Eldon Place. Metcalf recognised the filthy run-down terrace as they approached it. He had passed it many times on his beat, assuming it to be unoccupied. The shutters were always down and he’d never seen anyone go in or out. Even in such a deprived area of Liverpool, the house stood out as an eyesore. Its exterior black with dirt, it was in a dilapidated condition with numerous broken windows.

Although they could hear voices inside the house their urgent knocking brought no response. They climbed through the cellar window, into the yard, and then tried to gain access through the back door but it was bolted shut with a stick. Again Metcalf hammered loudly until finally a man’s voice from inside demanded to know who was there. ‘Police,’ Metcalf answered. ‘We just want to speak to you for half a minute.”

“What you have to say, say now,” responded the man, insisting he would only speak to him through the window. Metcalf sent the other police officer back to guard the front door while he continued to try to gain access.

Finally the door began to edge open silently. Metcalf forced it fully open to find a man, somewhat short in stature and shabbily dressed, still wielding the stick that had served as a makeshift bolt.

Entering the house, the sight that met his eyes was shocking.

In the kitchen, on a filthy broken bed, beneath a flimsy cover lay the body of Emma Aspinall, a year and ten months old. She was so thin and fragile that the bones protruded through her skin. Beside her, barely alive was a three month old baby, Thomas Ratcliffe Aspinall. Two more small boys, aged three and four, Albert James and Valentine Berry, lay uncovered at the bottom of the bed, emaciated, filthy dirty and completely naked. A third child, seven year old Elizabeth Jane, also lay on the bed.

Inside the fender enclosing the fireplace, seeking warmth from the embers that smouldered in the grate sat another small boy, six year old Daniel Burns, his feet resting on the ashes.

Three more children, fourteen year old Mary, twelve year old William Henry, and ten year old Charles, lay, covered only by a thin cloth, on a bare board on the stone-flagged kitchen floor. Seventeen year old John, who was so undersized the policeman took for a fourteeen year old, was lying across two chairs. The kitchen was bare except for the chairs, two old tables and a poker. The kitchen was as dirty as the street outside. Walking through to the parlour, Metcalf found a shabby sofa and a table. There were four other bedrooms, empty and unfurnished. There was no food in the house.

“What have you been doing to your wife and children?” demanded the horrified policeman. “Ask me no questions and I’ll tell you no lies,” came the gruff response from William Aspinall, who unlike his wife appeared to be completely sober.

Leaving Caldwell to monitor the house, now perceived as a potential crime scene, Metcalfe took Aspinall to the Bridewell for questioning From there he went on to the Northern Dispensary to fetch medical help.

Edward Brown, the assistant house surgeon on duty, came immediately to the house with Metcalf and was appalled by the scene that met him. He questioned Mary Aspinall who claimed that the baby, Thomas Ratcliffe, hadn’t had anything to eat for several hours. Brown felt that the skeletal figure of the dying child indicated starvation over a long period. He tended to the child as best he could and ordered that nourishment be obtained for him immediately.

The next official summonsed to the house was James Blake, the coroner’s beadle. He too looked around in horror, observing that one of the children, four year old Valentine Berry, was huddled naked on the chair like a dog. Mr Blake scheduled the inquest for Emma for the next day.

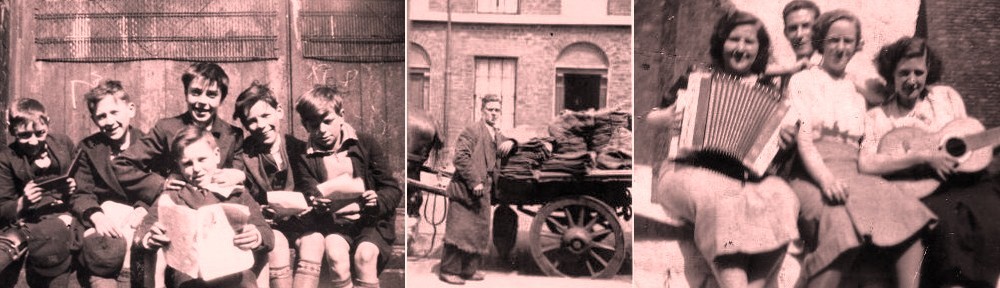

Brown went back to the surgery returning to the house in the evening to check on baby Thomas. He found him in much the same state as before. Thomas died that night and Brown’s next duty was to conduct a post mortem on the unfortunate child. Emma’s post mortem had already been carried out by George Kemp. On his return, Brown brought with him a fellow surgeon and lecturer in anatomy, Frederick Dicker Fletcher. Kemp meanwhile, arranged with John Atkinson of Manchester Street for photographs to be taken of the children and the conditions under which they had been living, both for his own interest, and to provide evidence at a later trial.

The first reports of what had happened came in the Liverpool Daily Post on Saturday. The Post article is a brief one and was either written prior to the inquest, based on statements made to the police, or put together very quickly just before the paper went to press. It detailed that Mary and William had given opposing versions of the events that led to Emma’s death, and that their daughter, Mary, had claimed that things started to go wrong about three years ago when her father had good reason to believe that his wife had been unfaithful to him, that she was still on ‘too intimate terms with a tradesman of this town’ and she continually drank to excess.

The inquests on Emma and Thomas Ratcliffe at St Georges Hall caused a sensation. The other children remained in a perilous state and not all would survive. The Coroner said it was the worst case he had encountered in 25 years. Both parents tried to apportion blame to each other for the tragic events that unfolded.

The Aspinalls were not a typical Liverpool working-class family. It emerged during the trials that far from being destitute, William earned a fairly generous wage of £75 a year working as a clerk for the London and North Western Railway company. His eldest son, John, also worked for the company earning eight shillings a week which he handed over to his parents.

The amount William was earning while his children were starving to death would have been more than the wages of the policeman who arrested him.

William started his working life as a gun maker, but was later employed as an assistant at the news room of the prestigious Lyceum Library in Bold Street, Europe’s first lending library, where his brother-in-law, John Perris, had worked for many years and earlier that same year had been appointed Head Librarian.

John Perris didn’t come from a wealthy family, but seems to have been a self-made man in the Victorian tradition and would have been quite prominent in certain circles in Liverpool. At the time, nobody appears to have made the connection between the two families.

A few years earlier, in 1851, the Aspinalls had been living at 55 Rodney Street, a prosperous area of Liverpool with fine Georgian properties. They had two servants in the household, one of them was John Perrris’s niece.

W. H. Duncan, appointed Liverpool’s first Medical Officer of Health in 1847, lived for a period at number 54.

Rodney Street is now a conservation area, considered nationally outstanding by the Historic Buildings Council, with more than its fair share of blue plaques and historic residents. British Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, was born at number 62 in 1809. The street was also the home of Victorian poet Arthur Clough, and later, Bloomsbury writer, Lytton Strachey. The studio of celebrated twentieth-century photographer Edward Chambre Hardman, next door but one to the Aspinall’s former home, is owned by the National Trust.

55 Rodney St where the Aspinall family were living in 1851

More Pages