Many Liverpool people have some Irish heritage – but distant enough that they no longer think of themselves as part of an ‘Irish community’. Even before the great famine, there was an Irish presence in Liverpool, with many coming over as seasonal labourers.

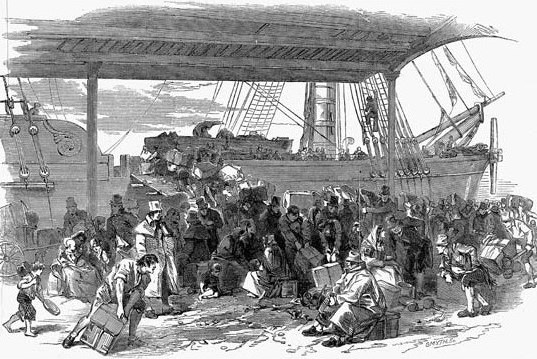

As the blighted crops failed in the 1840s, thousands of starving Irish streamed into Liverpool’s Clarence dock on small overcrowded steam ships. The police were instructed to count the number of arrivals. By their estimation, within the first eleven months of 1847, nearly three hundred thousand people landed at Liverpool from Ireland. A crude assessment was made of their likely destination. Those with luggage were deemed to be en route to America or elsewhere, but for the hundred and sixteen thousand observed to be ‘half naked and starving,’ Liverpool was probably the end of the line. It was expected that they would turn to the parish for their survival. Despite appeals, no financial help was made available from the government and the cost fell on the Liverpool ratepayers. This caused a great deal of resentment. Liverpool was already in a depression during the ‘hungry forties’. Although the Irish were British citizens, they were widely seen as a foreign invasion with a ‘foreign’ religion. Catholicism was viewed as unpatriotic, despite the presence of a small but longstanding tradition of English Catholicism. Britain was frequently at war with ‘Catholic’ Europe and Roman Catholics in Britain were suspected of giving their allegiance to the Pope instead of the Queen.

Almost a century of sectarianism followed Irish immigration into Liverpool, something now, thankfully, consigned to history. The building of new council estates which began in the 1930s, split up areas of segregated housing and brought divided communities together. And of course intermarriage helped blur the lines between different religious groups. Below are some newspaper articles that give a flavour of the negative response to Irish Immigration in the Nineteenth Century.

Liverpool Mail March 1851

During the famine years of 1847, 1848 and the greater part of 1849, the importation of Irish beggars into England and Scotland was fearful.

We read of swarms of locusts that eat up every green thing in Southern Africa; but although these vermin cause temporary loss they soon disappear; but the Irish beggars which infest Liverpool and its environs are worse than African locusts, for they bring filth, vice, and pestilence with them and they give to poverty all the odious and repulsive attributes of degraded—we might even say of beastly humanity.

We know that the poor shall always be in the land. We have our own poor people, the aged, the infirm, the destitute orphan, the child of misfortune, the helpless and bereaved widow, the blind, the lame, the palsied, and these unhappy beings of our own land and neighbourhood have strong, nay, irresistible, claims upon our charity. Every Christian has pleasure in assisting these unhappy ones; but the Irish beggar is generally an idle and worthless wretch, always a disgusting object, at least in England, and according to our English feelings.

But the famine years have passed away. Ireland they assure us is recovering; and yet these beggars still come in swarms of male shadows in indescribable rags, and horridly ugly barefooted nasty women carrying something like imps in bags at their backs.

This is pollution. Instead of exciting sympathy it produces nausea. Instead of awakening charity, it provokes feelings exactly the reverse. These wretches come we have said; but they are sent yes, sent to England by Irish squireens and municipal papists, mayors and magistrates to display their loathsomeness before our faces and beg if not steal upon our manor.

It is very hard that the inhabitants of Liverpool should be taxed to support these vagrants. Every ratepayer, although he may not know it has to keep an Irish beggar or two, month after month and, as it would now appear, year after year.

Liverpool Mail June 1850

The select vestry, on Tuesday, had its attention awakened to an evil with which the public has long been familiar; and from the continuance and increase of which the inhabitants of Liverpool have to suffer. We allude to the systematic importation of Irish, for the sole purpose of begging. Mr Savage, who introduced the subject, informs us that the week before last the number of this class of people who landed was 2,000; that last week 2,700 arrived, and on Sunday no fewer than 800.

These people must live. If they do not beg, they must steal. Work they will not; and the town is compelled to endure their loathsome filth and the burden of their importunity. It is of little use to return them to Ireland; another week brings them again to our shores, herded together like cattle, and conveyed on board the steamers for fourpence a head, the passage-money being furnished by those who are glad to rid themselves of their presence at so cheap a rate.

The cunning and lying of these mendicants has been very properly exposed, and it is to be hoped that the benevolent will no longer suffer themselves to be imposed upon. We are aware that there is much truth in the assertion made by Mr Earle as to the difficulty of inducing the ladies of Liverpool to forego those impulses of charity by which they are characterised; but, if they will look at home, much more worthy objects will be found upon whom they may bestow their bounty.

Liverpool Mail January 1847

We think the parish authorities have evinced a proper degree of forbearance in allowing the innumerable swarms of Irish beggars to infest the streets of Liverpool so long. But there is a limit to everything, and we have reason to know that unless the present hired invaders be returned to Dublin or Waterford, their numbers will be daily increased. It is a fact, that would disgrace any country but Ireland, that subscriptions are raised, by persons who call themselves the gentry of Dublin and other places, to pay the passage of these vagrants to Liverpool. Instead of having the pride or the honesty to maintain their own poor, as the poorest parish in England does, they export them in ship-loads to prey upon the humanity of this country. This conduct is not only indecent, it is criminal, and ought to be punished.

Dublin is a magnificent city, they tell us, full of magnificent buildings, full of lawyers and priests, it has a university full of students, a court and a castle, splendid levees and balls, dashing and money-spending soldiers, distilleries and breweries, and wine and spirit stores without number. Is it not a magnificent city? Where is there a shopkeeper or tradesman who does not keep a horse or a jaunting car, if not a box in the country?

In short, there are more saddle horses and car horses in the Irish metropolis than in all Lancashire. And yet, the gentry, and other wealthy inhabitants of this magnificent city, have the meanness to subscribe their shillings to transmit their own famishing poor to beg in England. And it is the women, too, chiefly, and young children they send, in one of the most inclement winters ever known. We have reason for believing that many of the most importunate of these women have borrowed children with them whom they pass off for their own.

Now, this sort of barefaced imposition—not so shameful on the part of the beggars themselves, as on the gentry who sent them—has been endured too, long. It is time that the streets should be cleared of them, and the parish authorities have the power to do so, which, we respectfully submit, they are bound to exercise.

It may have been observed by the inhabitants, and particularly by the shopkeepers and housekeepers who are molested by them from morning to night, that there is an absence of the male sex. Where are the men who are the reputed husbands and fathers of these women and children? Very possibly at work, earning at home fair wages out of the taxes of England, thus plundering us on both sides of the Channel, under the plea of famine.

We have no desire to send the hungry woman, or even the female impostor, empty away. Nor have we any wish to stay the impulses of genuine charity. But we deny that there is any charity in the case so long as the gentry over the water can live in the style they have done, and are doing at this very hour, and while there so much prosperity in the large seaport towns of Ireland, and while such an abundance of corn and all sorts of provisions being poured into that country from the supplies, and at the expense, of this.

Give these beggars, we therefore say, a loaf of bread and send them home. Thousands of them will go with money, in the usual way, concealed about their rags.